The sea, the seaweed and County Sligo

Surf is up at Enniscrone beach when I pull in beside a flat-roofed bathhouse overlooking the tidal foreshore below and endless golden dunes beyond. I’m here to meet Edward Kilcullen, who runs Kilcullen Seaweed Baths with the help of his son, Cain. “He’s out in the surf at the moment,” Edward tells me.

As we watch those waves roll in off the vast Atlantic coast, it’s easy to understand why this southwest Sligo beauty spot was one of Ireland’s best-loved Victorian seaside resorts. Back in the 19th century, Enniscrone became popular when people began embracing the benefits of sea swimming – and the complementary pursuit of seaweed bathing.

Enniscrone, County Sligo © Shutterstock

Edward enjoys a unique vantage point in Ireland’s long-evolving seaweed heritage and the bathing tradition at the heart of it. From where he stands in his family line, he can look back two generations to his grandfather, the one-time chauffeur at County Cork’s historic Liss Ard House with “a fascination for engines, for steam and for all things mechanical” who established this purpose-built seaweed bathhouse in 1912.

Edward can look forward too, over the shoulders of Cain – an ex-pro surfer and multiple national champion turned chief seaweed harvester for the bathhouse – to his 14-year-old grandson Finn, who is already taking an active interest in the family-run business.

Cain Kilcullen collecting seaweed at Enniscrone, County Sligo

Take a walk on the harbour pier in Enniscrone at low tide most days and you’ll see Cain in his tractor down on the mid-shore. He is there to harvest sackfuls of the wild fucus serattus seaweed, which has been used in the family bathhouse for over 100 years.

Cain picks what they will need in the bathhouse each day, which on a busy one might be a quarter of a tonne. It sounds like a lot, but Edward points out that in proportion to the abundant resource that’s there, it’s relatively little.

Cain Kilcullen surfing at Enniscrone, County Sligo

“It suits Cain,” his father says. “He’s totally at one with the sea. He just knows the tides in his mind. He’d be doing that as the tide is falling and the waves aren’t as good, and then when the push comes and the surf lifts, he’s ready to surf.”

Once the seaweed makes its short journey to the bathhouse itself, Edward explains, “we pack it into the equivalent of a three-gallon bucket, blast it with a quick jet of steam to release its alginates and throw it directly into the bath with heated sea water.”

The result is Ireland’s indigenous spa-like experience that leaves bathers’ skin feeling silky smooth, and has traditionally been valued as a cure for rheumatic pains and muscle aches.

Enniscrone, County Sligo

L-R: Kilcullen's Seaweed Baths; Edward Kilcullen; serrated wrack seaweed; the old Cliff Baths

When Edward’s grandfather got into the business of seaweed bathing, it had been booming for some time.

“About the middle of the 19th century our local landlord in the area, Christopher Guy-Orme, took to sea bathing, which had been in fashion ever since the Prince Regent had taken it up.” Edward points to the old Cliff Baths perched further along the sea wall.

He built a little two-room building there with a boiler and a bath, so when he came in from his swim someone would have a warm bath ready for him. That was just a private facility, but then around the 1870s he leased it out to a local family who extended it into a bathhouse offering hot seawater baths for people after their swims.”

Enniscrone was not alone in these dual pursuits of cold swims followed by hot baths, and the addition of fresh seaweed soon became de rigueur.

“By the end of the Victorian era there would have been seaweed baths in most of the traditional resorts: here in Enniscrone, Strandhill (County Sligo), Bundoran (County Donegal), Portrush (County Antrim). My grandfather came along as a newbie in 1912 with this place.”

Four generations of the Kilcullen family outside their seaweed baths at Enniscrone, County Sligo

Four generations later, Kilcullen’s bathhouse is still going strong, and its appeal has evolved over the years as much as endured.

“Traditionally it was older country people who came, when the harvest was done and their busy time of the year was over,” Edward says. “It was like a cure-all for the symptoms of rheumatism and arthritis – for aches and pains in their bones, basically.”

Holidaymakers kept Enniscrone busy before the post-harvest rush. “Every house in the village had people staying, even in ordinary houses you had people moving out into sheds to make room in the house for guests. It was an important earner from the early 1900s right up to the 1960s.”

At the height of the craze there had been several hundred seaweed bathhouses along the Irish coastline, with nine in Sligo alone. When it came to Edward’s turn to take over the business, however, traditional seaside resorts were competing with continental Europe made accessible by better travel connections, and seaweed baths had been deemed rather old fashioned. “By 1989, there were only two left in the country,” he recalls.

Reluctant to turn his back on his unique heritage (“we were the oldest, and the only one that had kept going through thick and thin”) Edward reinvested with a renovation. His timing proved lucky.

“People were starting to get interested in alternative therapies and health foods and healthy ways of living. We came in on that wave and it just seemed to click.”

Seaweed bath and steam box at Kilcullen's Seaweed Baths, Enniscrone, County Sligo

Edward cleaned up the original rooms, and added replicas of wooden 19th century steam boxes in each room so that bathers can alternate between the enamel baths, steam boxes and hot or cold showers.

“We still operate it very much as we always did,” he is proud to say. They still pump seawater at high tide onto the flat rooftop to be stored in large open 10-gallon tanks. That seawater is still heated indirectly with steam before filling the individual enamel baths as they’re needed. And the seaweed is still hand harvested sustainably from the same stretch of shoreline all these years later.

Mosaic tiles at Kilcullen Seaweed Baths, Enniscrone, County Sligo

“We have regulars who come on a weekly basis from 50 miles away for their seaweed baths. They feel it does them good.” While Edward says “it’s hard to nail down the science”, the positive side effects are generally attributed to the combination of seaweed and iodine-rich seawater. “The theory is that you absorb a certain amount of iodine content through your skin if you spend long enough in the bath,” Edward notes.

The oily silky texture of the alginate-rich seaweed is also high in iodine, calcium, magnesium, vitamins E and F, and for those who can brave it, it’s recommended to alternate between hot and cold temperatures. “The diehards here insist on getting under the cold shower afterwards, and the screams and roars out of them are priceless.”

Seaweed baths around Ireland

L-R: Wild Atlantic Way Seaweed Baths; Cliff House Hotel, County Waterford; Ice House Hotel, County Mayo; Voya Seaweed Baths, County Sligo

Seaweed baths are enjoying a revival in modern day Ireland, something Edward is delighted to support. “I’ve had lots of people come to find out how it’s done before opening up their own seaweed baths. The more there are, the better.”

There are now dedicated seaweed baths from Helvick Head in southeast Waterford to Ladies Beach in County Kerry’s Ballybunion and all the way up to Bundoran in County Donegal. You can choose between a shoreside seaweed bath in a mobile whiskey barrel hot tub, courtesy of Wild Atlantic Seaweed Baths who move around various locations, or a private seaweed bath in the comfort of your own hotel spa – or even your hotel room as at The Twelve in Galway.

Voya Seaweed Baths, Strandhill, County Sligo

Just outside of Sligo town in the popular surfing village of Strandhill, Voya Seaweed Baths offers a unique experience within a sleek modern spa, complete with low lighting and exclusive beauty products. Its sister company Voya Beauty was the world’s first range of certified organic seaweed-based cosmetics and now features in many of the best hotels, spas and stores around Ireland as well as exporting to Europe and the US.

Voya Seaweed Baths was opened up in 2000 in Strandhill by Neil Walton, a former professional triathlete. He first became fascinated by the sports therapy potential of thalassotherapy in the 1990s while undertaking a four-year sports scholarship at the prestigious Australian College of Physical Education at Sydney Olympic Park. On his return to Ireland, he headed to Edward’s baths in Enniscrone to see what the benefits of seaweed could bring to his sports recovery regime.

“I was absolutely amazed at how I felt afterwards,” he tells me several decades later, sitting outside Voya Seaweed Baths where builders are busy adding extra bathing rooms to keep up with a thriving demand. Today Voya’s 40,000 annual visitors range from couples on pampering dates to Buddhist monks from Cavan who believe in the grounding effects of the seaweed baths to sporting groups (“runners, cyclists, Gaelic football players”) who want to support their body’s post-training recovery.

Neil Walton, owner of Voya Seaweed Baths, on Strandhill, County Sligo

After his first experience in Enniscrone, the analytical sports scientist in Neil lead him to pursue a lifelong fascination with the power of seaweed in accelerating the healing process in sports training.

“The seaweed plant itself has the highest amount of micro-nutrition out of any plant on the planet,” Neil explains, thanks to being submerged most of its life in nutrient-rich seawater. A prolonged soak in seaweed-rich water allows our porous skin to absorb some of that micro-nutrition.

One of the nutrients is iodine, which Neil says is “fantastic for the hypothalamus gland” that controls our endocrine system and coordinates the body's functions to maintain homeostasis during rest and exercise.

Just as our skin’s pores open in hot water, so does the seaweed. “It opens up exactly like your skin and the alginate comes out nearly like a sweat.” A hot soak in a regular bath will aid a certain level of recovery thanks to the heat conducted into your sore muscles. Those alginates also allow a seaweed bath to get quite viscous.

“So you get more of that conductive heat effect, plus you have the benefits of the micro-nutrition and the alkaline quality of the water, which helps to buffer the lactic acid within your system and bring down the inflammation in parts of your body.”

Strandhill, County Sligo © Fáilte Ireland

Neil is also an advocate for the benefits of counterbalancing our body’s positively charged ions. “Our body works on positive and negative ions. The more negative ions, the healthier you are; the more positive, the more compromised your immune system is. Sea water and seaweeds are very heavily negatively charged, so when you go into the sea or a seaweed bath you change the actual formation of the electrically-conductive charge of your body.”

All those micronutrients make seaweed a precious natural resource, which is why Neil is careful to harvest it with sustainable methods that allow for rapid regeneration at their harvest sites. The son of an organic horticulturist, the late Mick Walton, who broke records with his prize-winning vegetables, Neil also knows well how powerful seaweed can be as a natural fertiliser for soil.

As at Enniscrone, where the post-soak seaweed from Kilcullen's bathhouse is valued as an organic fertiliser for the pasture at the family’s farm, the spent seaweed from Voya Baths in Strandhill is in popular demand with local farmers and community gardeners.

Serrated wrack seaweed, Voya Seaweed Baths, Strandhill, County Sligo

Indeed for many of the coastal and island communities along the windswept Wild Atlantic Way coastline, there was a strong tradition of using seaweed as a fertiliser for agriculture, allowing them to bolster the productivity of the poor west coast soils enough to keep themselves fed.

As Edward Kilcullen says, “seaweed used to be considered a very valuable resource for the farms” and having access to it was key. Historical records such as Griffith’s Valuations, a valuation of national property carried out in the 1850s, show that coastal land had a much higher valuation than land inland.

As with other valuable resources in the 19th century, it was managed carefully by the local landed gentry. “If one of those big drifts of seaweed would come in on the shore after a storm, the people would be allocated a certain area along the beach to harvest.”

Seaweed cuisine in Ireland

L-R: Seaweed on the menu at Aniar, Galway city; wild seaweed on Streedagh Strand; carrageen moss © Shutterstock; seaweed foraging with Irish Seaweed Kitchen, County Sligo

Another way to absorb the highly concentrated bioactive micronutrients of seaweed is by eating it as is, or in food. In parallel to the modern revival in seaweed bathing, edible sea vegetables have been playing an increasingly important role in Ireland’s modern food culture.

Seaweed features as a convenient seasoning in home cooking and a valuable ingredient in the rapidly developing functional foods industry, as well as appearing on menus from fine-dining restaurants to casual cafés.

On the terroir-inspired tasting menu at Galway’s Michelin-starred Aniar Restaurant, chef JP McMahon might pair clams with pepper dulse and salted gooseberry, or smoked cheese with savoury kelp.

At Sligo’s Osta Café, chef-owner Brid Torrades tosses fresh salad leaves with young sea spaghetti and dulse topped with air-fried nori crisps, or uses dulse to season everything from smoked haddock chowder to chocolate brownies.

When she ran Glebe House at Collooney in the 1990s, Brid loved to use carrageen moss as a natural setting agent for her homemade crab mousse, which was inspired by the traditional blancmange-style carrageen moss milk pudding that takes pride of place on the famous dessert trolley of Ireland’s seminal farm-to-fork restaurant at Ballymaloe House in County Cork.

Mullaghmore Head and Classiebawn Castle, County Sligo

At Eithna’s By The Sea in Mullaghmore, chef Eithna O’Sullivan bakes a seaweed bread daily, along with treats like chocolate meringues with nori and her famous fish and chips, featuring cod or haddock coated in a seaweed-seasoned polenta and rice flour crumb.

It’s not just Irish chefs who have been rediscovering the joys of cooking with edible seaweed. In 2009, Eithna helped to test and develop recipes for a ground-breaking cookbook published by a local doctor and longtime seaweed forager, Dr Prannie Rhatigan.

Many of Prannie’s happiest childhood days were spent with her father gathering the wild edible seaweeds that her mother would then incorporate into their daily diets, and after she completed her medical training and moved back to her coastal community, Prannie became fascinated by the (albeit slowly) emerging science about the seaweeds that she describes as “nutritional powerhouses”.

Seaweed champions

L-R: Eithna O'Sullivan, Eithna's By the Sea, Mullaghmore, County Sligo; Dr Prannie Rhatigan, doctor, seaweed forager and author; seaweed-based dishes from Eithna's By the Sea; Mullaghmore Harbour, County Sligo

There are more than 500 large marine algae that have been identified off the shores of the island of Ireland – in fact, the cool clear waters of Rathlin Island of the County Antrim coast produce some of the best quality kelp in the world. Prannie identifies more than 30 of these seaweed types as suitable for culinary use, each with their own unique flavour, texture and nutritional make up.

These feature in her laminated pocket-guide to edible seaweeds, while her two cookbooks – Irish Seaweed Kitchen (2009) and Irish Seaweed Christmas Kitchen (2014) – feature hundreds of delicious traditional and contemporary seaweed recipes to inspire home cooks.

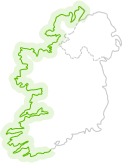

Prannie is one of several experts who now lead regular seaweed foraging walks along some of Ireland’s 1,450km coastline. Her favourite place to bring people is her own local Streedagh Strand near Grange, just north of Sligo town.

It’s a beach made famous by its shipwrecks – at low tide the skeletal remains of the 18th century Greyhound of Whitby protrude from the sands, while two wrecks of the doomed Spanish Armada fleet of 1588 lie submerged offshore – but it’s the seaweeds themselves that prove the real treasures, from the warming heat of pepper dulse to the savoury sea truffle.

Streedagh Strand, County Sligo

These foraging walks have proved popular with locals and tourists alike, and Prannie has noticed a dramatic shift in people’s familiarity with the different types of edible seaweeds and their uses.

Seaweeds are becoming a more everyday ingredient once again, and you can now pick up high-quality, conveniently milled, mixed dried seaweed seasoning in most local supermarkets, harvested at one of more than two dozen licenced seaweed aquaculture sites along the Irish coastline.

Most of these are small scale family-run affairs, and many are now second generation. Manus McGonagle of Quality Sea Veg grew up harvesting seaweeds with his father off the Donegal coast at Burtonport. “I was just a child when my dad first took me harvesting in the late 1960s in ‘a flat’, one of the 12-foot rowing boats unique to the area,” he recalls.

Manus went on to complete a degree in engineering and returned to his family heritage when he founded Quality Sea Veg in the late 1980s to meet the increasing demands for sea vegetables in Ireland and Europe.

Burtonport Harbour, County Donegal

“In the last 10 years seaweed has become huge in food, and large-scale multinationals are seeking out Irish seaweed for its quality,” says Damien Melvin of Carraig Fhada in west Sligo. Damien is also carrying on the family tradition, having taken over the running of the seaweed harvesting business that his father Frank Melvin started in the late 1980s. “It’s come a long way from one man harvesting a bit of seaweed and selling it into local shops,” he laughs.

Much has changed in Ireland over the generations and the use of seaweed has ebbed and flowed but it happily looks set to retain a proud place in the evolution of the island's unique coastal communities.