Dublin’s literary pubs

Peace is an elusive state of mind. Outside of the family bathtub, one of my favourite places to find solace is in the pub. An odd thing to say, I know. He goes to a pub to find peace?

But when I look back on decades past, I realise that some of my most tranquil moments were in Irish pubs, a pint of Guinness or a glass of Irish whiskey beside me, pen in hand, writing whatever stories were in my mind.

The pub and the pen. They’ve always gone hand in hand. Especially in Dublin. The written word, creative fiction, literature, is such a massive part of Dublin’s DNA.

That’s why the city is so celebrated for its playwrights, poets and authors, from Jonathan Swift to Oscar Wilde to Sally Rooney.

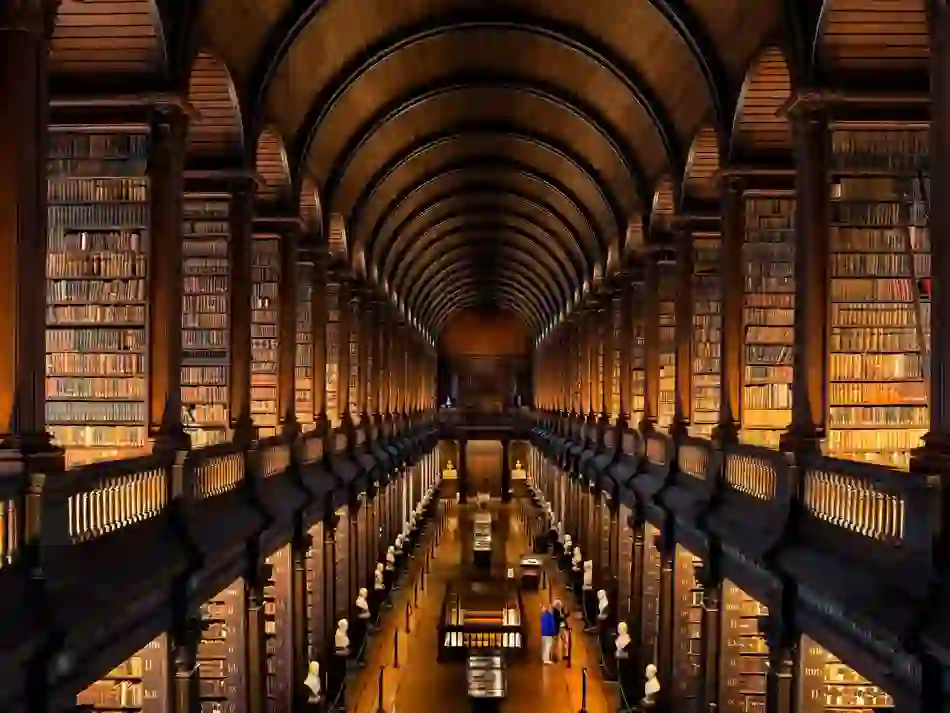

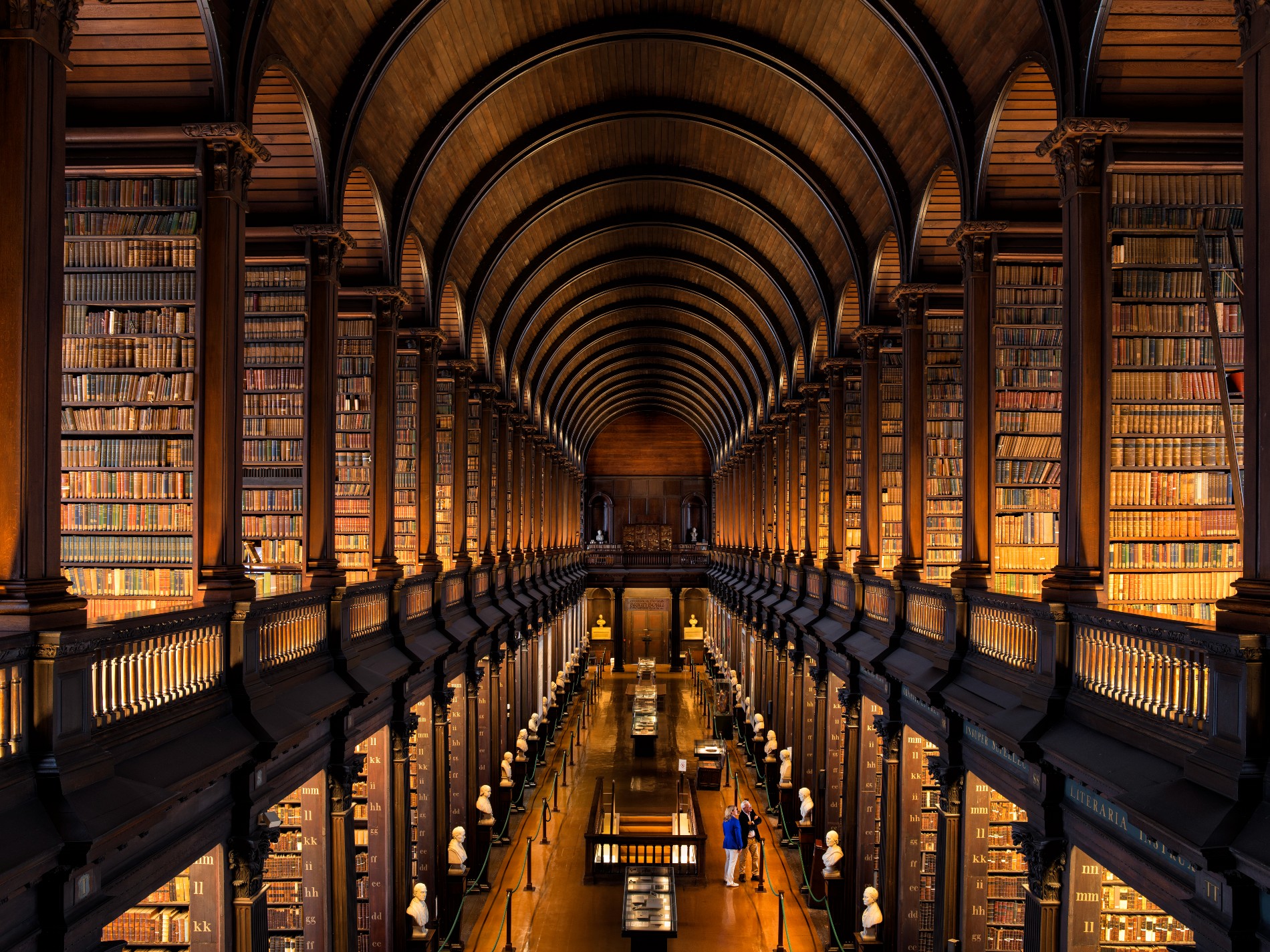

The Long Room, Trinity College Dublin © Tourism Ireland

I suspect the Irish love of fiction has its origins with the early Christians monks who conjured such magical stories as St Brendan’s voyages on the Atlantic Ocean, or the scribes and illuminators who collaborated on gob-smackingly beautiful works such as the Book of Kells, a precious ninth century manuscript on show at Trinity College Dublin.

Indeed, to get a sense of the depth of Dublin’s bond with the written word, just go into the Old Library at Trinity, close your eyes and inhale the musty aroma of 200,000 ancient books. Since 1801, the college has been legally entitled to a free copy of every single book published in Ireland or the United Kingdom.

You’ll get the same sensation if you swing by Narcissus Marsh’s wonderful library by St Patrick’s Cathedral, or the Edward Worth Library beside Kilmainham Gaol.

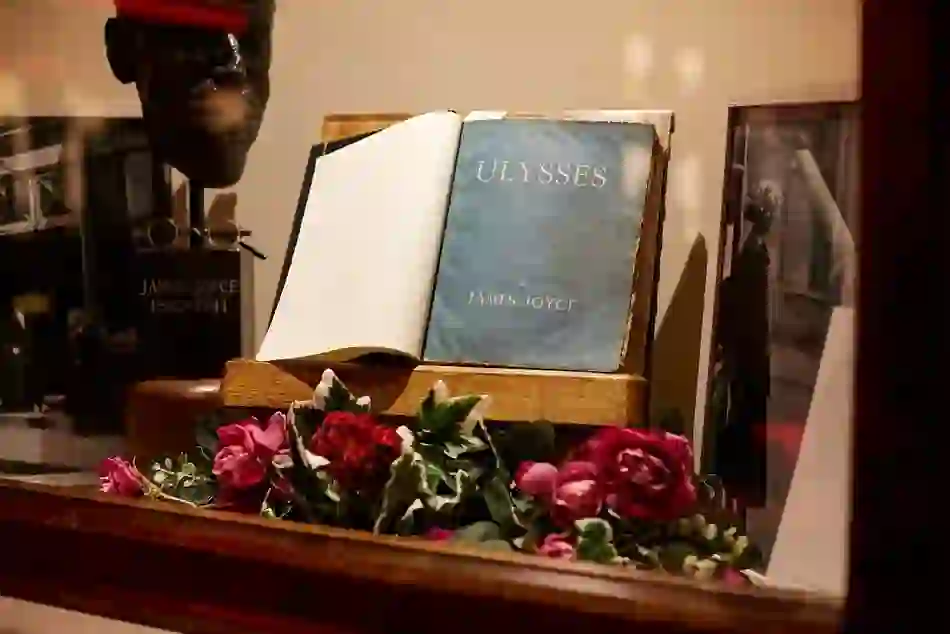

Book of Kells Exhibition, Trinity College Dublin

That’s why Dublin is a UNESCO City of Literature, with an annual book festival, as well as an unofficial literary holiday every 16 June, known as Bloomsday, in honour of James Joyce's acclaimed novel, Ulysses, which was published over 100 years ago.

That’s why three of the bridges that span the River Liffey are named for writers: Joyce, Sean O'Casey and Samuel Beckett.

That’s why the city is home to over 40 publishing houses; why Dublin City Council offers one of the richest literary prizes in the world the – €100,000 Dublin Literary Award; and why Dublin was home to all four island of Ireland-born winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature: Beckett, George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats and Sandymount-resident Seamus Heaney.

Literary greats

L-R: Marsh's Library; Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI); the James Joyce Centre; the Samuel Beckett Bridge

Dublin has been famous for its writers for hundreds of years. The principal entrance to Trinity College is flanked by statues of two past students who became literary icons in the 18th century: Edmund Burke, the Enlightenment champion, and Oliver Goldsmith, a genius at poetry, novels and plays.

Goldsmith was no model student, mind you. An enthusiast for taverns, he spent his Trinity days learning how to drink, dress smart, sing Irish airs, play cards and master the flute, shortly before he was suspended.

One of his favourite haunts was The Reindeer near the present-day Four Courts on Inns Quay. When short of funds to pay his drinks tab, he would pen a ballad for “street singers” to sing in the pub and raise the necessary money.

The Brazen Head, Lower Bridge Street

The Reindeer is no more but of around 750 pubs across Dublin today, there are plenty that will connect you to the wonderful world of Irish writers.

The Brazen Head claims to be Dublin’s oldest pub, originating as a hostel by the city gates for people seeking to enter Dublin the following day. Its patrons included Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels, who was very particular about his beer. Writing under the pseudonym of Geoffery Jinglestaff, he lamented a brief trend for London-brewed porter in Dublin pubs in 1736, declaring it unfit for “any Creature above a Swine”.

Twenty years later, the eccentric novelist Thomas Amory recalled “many a happy evening” he spent in a “charming little public house” known as the Conniving House, located near present-day Sandymount Green. His companions were “the famous Larry Grogan, who played on the bagpipes extremely well [and] dear Jack Lattin, matchless on the fiddle … The ale here was always extraordinary, and everything the best.”

A plaque outside the Bleeding Horse on Camden Street honours horror-writing author Sheridan Le Fanu who set part of his 1845 novel The Cock and Anchor in the pub. Le Fanu’s Gothic novella Carmilla, one of the earliest works in vampire fiction, inspired Dublin-born Bram Stoker to write the world famous, genre defining Dracula. Stoker, whose spirit lives on with the Bram Stoker Festival held in Dublin every Halloween, sank his teeth into a pint or two at Toner’s on Baggot Street.

Literary trivia doesn’t come much fruitier than the day Bram Stoker married Oscar Wilde’s ex-girlfriend at St Ann’s Church on Dawson Street. Arguably the most flamboyant Dubliner of all, it was Wilde who once described work as “the curse of the drinking classes”.

He grew up at No. 1 Merrion Square and is said to have enjoyed a drink or two in nearby Kennedy’s of Westland Row, where a mural highlights its many literary links including Joyce, who once staged Wilde’s play, The Importance of Being Ernest, in Zurich.

Julianne Mooeny Siron, Marsh’s Library

“The Dublin pubs were always a great leveller, open to all and everyone,” says Julianne Mooney Siron, director of the Dublin Book Festival. "Many of the pubs frequented by writers still retain that old-world feel. It’s easy to imagine Joyce, Wilde and others sitting around discussing their works and watching the world go by, in search of inspiration for their poems and stories.”

Kennedy’s is located just east of Finn's Hotel, now shut, where Joyce’s future wife Nora Barnacle worked as a chambermaid. Their lives were fictionalised by Nuala O'Connor in Nora: A Love Story of Nora Barnacle and James Joyce. This book is the 2022 selection for One Dublin One Book, an acclaimed initiative spear-headed by the Dublin UNESCO City of Literature office.

Ulysses on display in Davy Byrnes, Duke Street

In 1922, Dublin-born James Joyce published Ulysses, the seminal book of 20th century Irish literature, in which we follow Leopold Bloom, a Jewish everyman, as he rambles around Dublin on 16th June 1904. “Good puzzle would be to cross Dublin without passing a pub,” remarks Bloom.

As Christopher Morash, the Seamus Heaney Professor of Irish Writing at Trinity College Dublin, observes: “It took almost 90 years (and help from a computer) before someone figured that puzzle out."

A painting of James Joyce in Kehoe's

Joyce’s works were profoundly entwined with Dublin pubs. While he drank, he listened. To the language and the banter, the nuances, the accent, the wit of each story told, and somehow he stored that discourse to reincarnate in future novels. The snippety language of his dialogue, internal and external, literally sounds like what you would hear if you walked through a crowded pub and processed extracts of all the conversations going on all around you.

“It is not for nothing that Joyce set his final novel, Finnegan’s Wake, in a pub,” adds Professor Morash. The gallant few who have made it through that novel might consider a visit to Mullingar House, Chapelizod, west of the city centre, which has strong claims to be that very pub.

Davy Byrnes, Duke Street

The principal pub for Joycean enthusiasts is Davy Byrnes on Duke Street, where the eponymous owner, “in tuckstitched shirtsleeves”, served Bloom a gorgonzola cheese sandwich and a glass of Burgundy. This colourful pub had been a haunt of the literati since the Gaelic Renaissance. It also features in Edna O’Brien’s trilogy, The Country Girls, when the protagonists Baba and Kate pop in to share a glass of Pernod.

Inside Davy Byrnes, Duke Street

Joyce abandoned Ireland in 1904 but his homeland was never far from his mind. In later life, he even proposed to Guinness that they replace with their Guinness is Good for You slogan with a slogan of his own, “Guinness – the free, the flow, the frothy freshener!” It didn’t catch on.

Joyce’s foremost researcher when he wrote Finnegan’s Wake was Dublin-born Samuel Beckett, who would win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969. The friendship waned after Beckett rejected the advances of Joyce’s daughter Lucia.

Beckett was wary about the “indiscretion and broken glass” of Dublin pubs but he is also said to have drunk in Kennedy’s on Westland Row while studying literature at Trinity College in the 1920s.

The Winding Stair Restaurant and Bookshop, Ormond Quay

The poet WB Yeats, who won his Nobel in 1923, was also hesitant about pubs but Oliver St John Gogarty got him through the doors of Toner’s of Baggot Street at least once. If it is Yeats you seek, The Winding Stair restaurant on Ormond Quay takes its name from one of his poems and offers fine views over the Liffey.

In 1925, the literary Nobel went to another Dubliner, the playwright George Bernard Shaw, author of Pygmalion. Shaw’s last Dublin home on Harcourt Street is now incorporated into the Harcourt Hotel, home of the lively D Two Bar.

Most of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916 were poets and writers. That did not prevent the Irish government enacting the Censorship of Publications Act in 1929, which gave the state the right to prohibit any writings deemed obscene or indecent. Such legislation was prompted by the Catholic hierarchy’s wish for “a simple measure of moral hygiene” following “a veritable spate of filth never surpassed”.

Frustrated by the inability to have their work published, several writers abandoned Ireland in the 1930s, including Beckett and Liam O'Flaherty, whose novel The Informer would be made into an Oscar-winning Hollywood thriller directed by John Ford.

Mulligan’s, Poolbeg Street

Meanwhile, other writers, editors and journalists began to conglomerate in the pubs around the headquarters of Dublin’s leading newspapers.

Hardy, old-style pubs such as The Palace Bar on Fleet Street and Mulligan’s of Poolbeg Street, which still exist, became vibrant hubs of underground dissent for a new generation of creative souls (predominantly men – women were still all but prohibited from pubs).

They found their muse amid the smoke and the sawdust, the spit-flecked floorboards and the tobacco-stained walls, the rudimentary furniture, the whiskey shorts, the pint of plain.

As The Irish Times correspondent Kevin Lehane fondly recalled, “Patrick Kavanagh could be heard discoursing in McDaid's of Harry Street on such esoteric subjects as professional boxing, the beauty of Ginger Rogers, or the dire state of Gaelic football in Ulster.

Flann O'Brien could be heard in Neary's or the Scotch House on any subject known to man … Brendan Behan could be heard everywhere.”

Lehane also observed how such men regarded each new pint as something “to be contemplated as well as to be drunk”.

The Shelbourne Hotel, St Stephen's Green

A more opulent enclave was the Shelbourne Hotel, which also features in Ulysses. The 5-star hotel has hosted stars from Rudyard Kipling to Charlie Chaplin, Julia Roberts to Seamus Heaney.

Its history was written by the Dublin-born author Elizabeth Bowen while the hotel’s Horseshoe Bar is the setting for Edna O’Brien’s 2011 short story Send My Roots Rain, in which an ageing librarian waits for Ireland's pre-eminent poet to turn up.

Kavanagh’s favourite pub was The Palace Bar, which he hailed as “the most wonderful temple of art. That's where the gabble of poetry was to be heard.” One of his most constant companions at The Palace was Brian O’Nolan, a tremendous satirist who wrote under the pen names of Flann O’Brien and Myles na gCopaleen.

Another Kavanagh stronghold was The Waterloo on Baggot Street, a part of the city immortalised by the poet, which stands midway between his seated statue by the Grand Canal and Raglan Road, the setting for probably his most famous poem.

Grogan's (the Castle Lounge), South William Street

Flann O’Brien set one of the most hilarious sections of his metafiction masterpiece, At Swim-Two-Birds, in Grogan’s of South William Street, where three men experience a “sense of physical and mental well-being” by “putting glasses of stout into the interior of [their] bodies.”

In truth, there were multiple pubs across Dublin which can justly claim that Kavanagh and O’Brien were “notable patrons”, alongside other pint-swillers including Anthony Cronin, JP Donleavy and Brendan Behan.

Simon O'Connor, Director of MoLI, St Stephen’s Green

Behan was the biggest boozer of them all. A word search through his “Interviews and Recollections” brings up the word “pub” 88 times. “I like pubs because I like people,” he said on one occasion. And on another, “I’m a drinker with a writing problem”.

Behan, whose most famous works include Borstal Boy and The Quare Fellow, was a house painter by profession. In the early 1960s, he offered to paint a fresh sign on The Cat and Cage in Drumcondra, which had been a haunt of Sean O’Casey’s too. He and a pal did such a bad job that the owner only paid half the fee; they were eventually paid the other half in liquor.

That said, Simon O’Connor, director of the Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI) on St Stephen’s Green, stresses that “we should not allow the drunken past of our artists to overshadow the great art they made. Hilarious a drunk as Behan was, it was drinking that killed him, extinguishing an incredible artistic talent long before his prime.”

Scenes from Dublin pubs

L-R: McDaid's, Harry Street; Kehoe’s, South Anne Street; the bar at McDaid's

There were some pubs that Behan, Kavanagh and company visited more than others. Davy Byrnes was again high on the list. Neary’s of Chatham Street, Kehoe’s of South Anne Street and The International on Wicklow Street were also favoured. However, their literary mecca was the narrow, high ceilinged McDaid’s on Harry Street.

The cash till at McDaids went into overdrive when Dublin bohemian John Ryan (a founder of Bloomsday with Flann O’Brien) established a short-lived literary journal called Envoy on nearby Grafton Street. With Kavanagh, O’Brien, Donleavy, Behan and even Beckett as contributors, the gentlemen unsurprisingly adjourned to McDaid’s at lunchtime daily to conduct their business in more salubrious surrounds for the remainder of the day.

The Long Hall, South Great George’s Street

“McDaid's was never merely a literary pub,” recalled Cronin. “Its strength was always in variety, of talent, class, caste and estate. The divisions between writer and non-writer, bohemian and artist, informer and revolutionary, male and female, were never rigorously enforced.”

Another pub Behan knew well was The Long Hall on South Great George’s Street, which was across the road from Dockrells, the hardware store where his father worked. This was where Dublin rock legend Phil Lynott sank his stouts during the filming of the video to Thin Lizzy’s Old Town.

On the wall is a short poem by Frank Holt called In Praise of Guinness:

“In Dublin there’s a beauty that has no match,

It is brewed in St. James’s, then thrown down the hatch.”

Embracing the culture

L-R: The Ginger Man, Fenian Street; The Ginger Man street sign; “The Doc” in Mulligan's; Toner’s

The Dublin writers found a new enclave when John Ryan himself took over The Bailey in Duke Street. Ryan claimed to have accidentally purchased the pub at an auction when he went to buy a kettle. He installed the original hall door of 7 Eccles Street, home of Leopold and Molly Bloom in Joyce’s Ulysses, in the pub.

Another writer who drank alongside Behan and O'Brien was the American-Irish author JP Donleavy, whose controversial 1955 classic The Ginger Man has sold over 45 million copies and never been out of print.

The book, which gave its name to The Ginger Man pub on Fenian Street, near Merrion Square, follows the exploits of Sebastian Dangerfield, a misogynistic student bum, who visits, amongst others, Mulligans, Toner’s, The Bleeding Horse and Finnegan’s in Dalkey.

Meeting the locals

L-R: Hugo Jellett in Kehoe’s, O’Neill's, The Palace Bar, The Stag’s Head

In the next generation, Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon, Derek Mahon and Michael Longley - the award-laden poets who led the Ulster Renaissance in the 1960s - often met in the cocktail bar of O’Neill’s of Suffolk Street while they were students at Trinity. Also present was the charismatic Brendan Kennelly, (later Emeritus) Professor of Modern Literature at Trinity College.

The allure of the pub has always been contagious to writerly minds. Hugo Jellett, director of the Festival of Writing and Ideas, worked with Lilliput Press and O’Brien Press during the 1990s.

"I spent my 20s in literary strongholds like Kehoe’s and Hartigan’s and Bowe’s. Between the Flann O’Brien flounce and Behan’s ghost and the emergence of Colm Tóibín, John Banville, Anne Enright, Sebastian Barry and Roddy Doyle, I got stuck in it forever.

I wanted to be a barrister or something useful. Instead I started a literary festival. Dublin does that to you. It comes to possess your literary bones.” “Pubs are so much as part of the city that it is almost impossible to pin down any one thing that they have meant to its writers over the years,” adds Morash. "Kavanagh once observed that 'a poet needs an audience' and, for some, pubs have been a stage, while for others they have been a quiet place to meet other writers.

"There have also been writers for whom the Dublin pub has simply provided a setting where anyone and everyone might appear.”

Roddy Doyle’s ever-evolving novella/ two-man play Two Pints could feasibly be set in any pub, while scenes from the fabulous film version of his book The Commitments were shot at The Camden on Lower Camden Street.

The Blackbird Pub on Rathmines Road Lower doubles up as the student haunt where Marianne, Connell and their pals shoot some pool and drink pints in the TV series of Sally Rooney’s Normal People, the 2018 Costa Book Awards winner.

In Belinda McKeon’s novel Tender, the protagonist conducts a fabulously excruciating interview in the much-loved Library Bar of the Central Hotel on Exchequer Street.

City Hall, Dame Street

There are literary links all over the city. The Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle, whose family was Irish, is honoured by Doyle’s Corner, the junction of the Phibsborough and North Circular Roads on the northside of the river.

Nearby Blessington Street is the birthplace of Dame Iris Murdoch, the first Irish writer to win the Booker Prize (for The Sea, The Sea, in 1978). Several scenes from Christine Dwyer Hickey’s acclaimed novel Tatty, the 2020 One Dublin One Book selection, are set in Myos in Castleknock.

Colm Quilligan started the award-winning Dublin Literary Pub Crawl in 1988. Since then three quarters of a million people have embarked upon the two and a half hour odyssey.

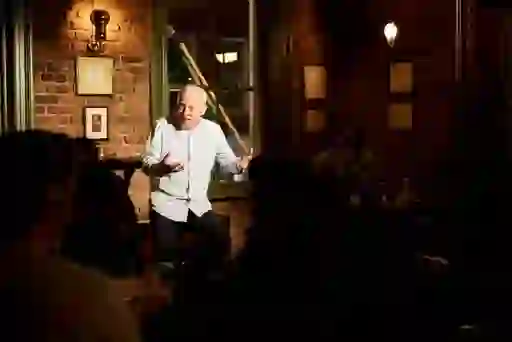

Colm Quilligan performing at The Duke, Duke Street

“We do focus on Joyce, Wilde, Beckett and Yeats,” he says, "but it’s more than a Dead Poet’s Society. We go where contemporary writers go, and we bring in stories about present-day authors. The Duke, where we start, is just around the corner from Hodges & Figgis, the iconic Dublin bookshop. That’s where authors such as Anne Enright, Roddy Doyle and John Boyne often hold their book launches and the post mortem for those launches is inevitably held at The Duke.”

If you should see someone reading in the pub, perhaps its MoLI director Simon O’Connor, who remarks: “People often forget that pubs are great places to read, particularly in the daytime if you can find one without music or sport on a television. I always remember finishing an Edna O'Brien collection over a pint of stout one afternoon, the bells of St Patrick’s ringing in the final paragraphs, and feeling like I had died and gone to heaven.”

The Duke, Duke Street

Dublin Literary Pub Crawl

A fabulous opportunity to visit some of the pubs mentioned in this feature, and to learn the literary connections. The Dublin Literary Pub Crawl actors perform extracts of various works as they escort visitors from bar to bar, adding in biographical details of the writers along the way. It’s educational but humour is key. Commences nightly at 7:30pm (summer schedule begins on April 1) from The Duke on Duke Street.

James Joyce Pub Crawl

John Geraghty and Luigsech Bennett run the James Joyce Pub Crawl and bring private groups by appointment to a handful of pubs associated with Joyce, depending on the day of the week and how busy they expect places to be on a given day. “It's a partial potted history of Joyce's relationship with Dublin pubs,” says John, “and mostly an enjoyment of the pubs themselves.”

Dublin Book Festival © Tourism Ireland

Away from the pub

International Literature Festival Dublin

Every May in various locations around the city; ilfdublin.com

Bloomsday

An annual celebration of the life and work of James Joyce, which takes place on 16 June every year; bloomsdayfestival.ie

Dalkey Book Festival

Irish and international authors descend on the pretty village of Dalkey for this buzzing annual festival in June; dalkeybookfestival.org

Dublin Book Festival

Each November in venues throughout Dublin and online; dublinbookfestival.com

Dublin's literary hotspots

Other key locations for literature lovers include the National Library of Ireland and the Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI) on St Stephen’s Green.