$name

“It’s one of the most dangerous stretches of water in Europe,” says our skipper, Billy. “The currents here can be quite bad, the water rushes in like a river.” We’re bobbing about in the Blasket Sound aboard the “Peig Sayers” Stormforce 11 RIB speed boat as part of the Great Blasket Island Experience tour.

Ahead of us lies the cloud-darkened mass of the Great Blasket Island, which writer Seán Ó Faoláin once described as “wallowing like a whale in the darkening sea”. Its steep slope is strewn with broken-down cottages; a place suspended in the past.

The weather hasn’t been on our side for the trip out here. For more than an hour, we’ve rolled over silver-tipped Atlantic waves that have slapped the boat and caused varying degrees of sea-sickness in some of the passengers on board. We’ve passed ancient forts, jagged sea cliffs and majestic rock formations along the coast of the Dingle Peninsula, but the green faces tell their own story.

“Just sit down when you get onto land,” Billy says kindly as he helps the unwell onto a dinghy for the final journey to the island. “That’s all you can do… it will pass.”

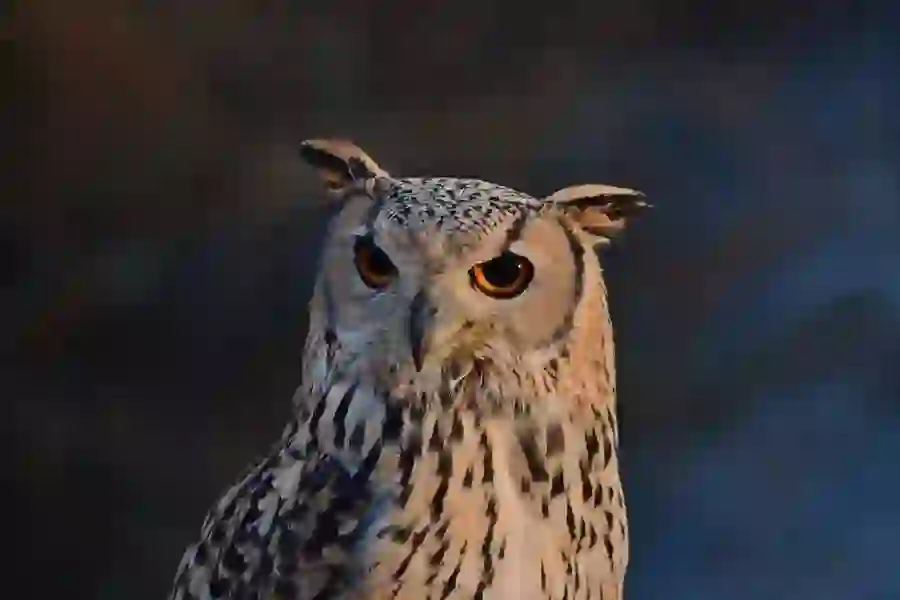

Great Blasket Island © Tourism Ireland

For centuries, the Great Blasket Island was home to a community of people for whom crossing these waters was a way of life. It’s thought that the islands were first inhabited in the 1700s, but by 1954, the population had dwindled from a peak of 176 in 1916 to just 22 – and they were ready to depart for a new life on the mainland.

“There was no option but to leave,” islander Gearóid Cheaist Ó Catháin told the Irish Times in 2014. The isolation of the Great Blasket locals was tested by the death a young man from meningitis; bad weather meant he couldn’t access medical care, nor could they access a coffin for him after his death. “People got scared. They were getting old and the isolation started to get to a lot of them.”

Dinghy to the Great Blasket Islands

Crossing in the dinghy under an ashen sky, it’s easy to appreciate a small bit of the unpredictability of life here, where summers must have been glorious and winters dark and brutal. A simple landing on the island at the small harbour is an adventure in itself. After that, it’s a steep hike up the slippy, jagged rocks, followed by a sharp grassy incline that causes even the fittest of the group to pause for breath.

Billy helps visitors into the island