A Titanic tale in Belfast

Two coins bounce off a wall in Belfast. I’ve thrown one; tour guide Donal Kelly the other. Pitch and toss, the game is called, and the idea is to throw your coin so that it bounces back, landing as close to the wall as possible.

“Closest to the wall, winner takes all”, is the rhyme that goes with it. It’s as simple and addictive a game today as it was over a century ago, when Donal’s great-grandfather played with fellow workers at the Harland and Wolff shipyard.

Today, we’re using a wall on the restored slipways and plaza beneath Titanic Belfast, the iconic, 21st century tourist attraction. But back then, they might have stooped beneath a very different structure: the hull of RMS Titanic herself.

Belfast's Titanic Quarter, with the dry dock, pumphouse and Harland and Wolff cranes, Sampson and Goliath, in the background © Visit Belfast

Titanic: made in Belfast

Titanic set sail from Southampton, England on April 10, 1912. She picked up passengers at Cherbourg in France and Cobh (then Queenstown) in Ireland. Her destination was New York.

But the most famous ship ever to set sail was built in Belfast, at Harland and Wolff on Queen’s Island. And, as locals like to say, with dark Northern Ireland wit: “She was all right when she left here.”

Donal is a guide with Belfast Mic Tours, and he takes me along the Maritime Mile walk on the part of Queen’s Island now known as the Titanic Quarter. As we walk, he shows me maps and photographs from late Victorian and Edwardian times, evoking an industrial city with puffing chimneys and thriving shipbuilding, linen, tobacco and whiskey businesses.

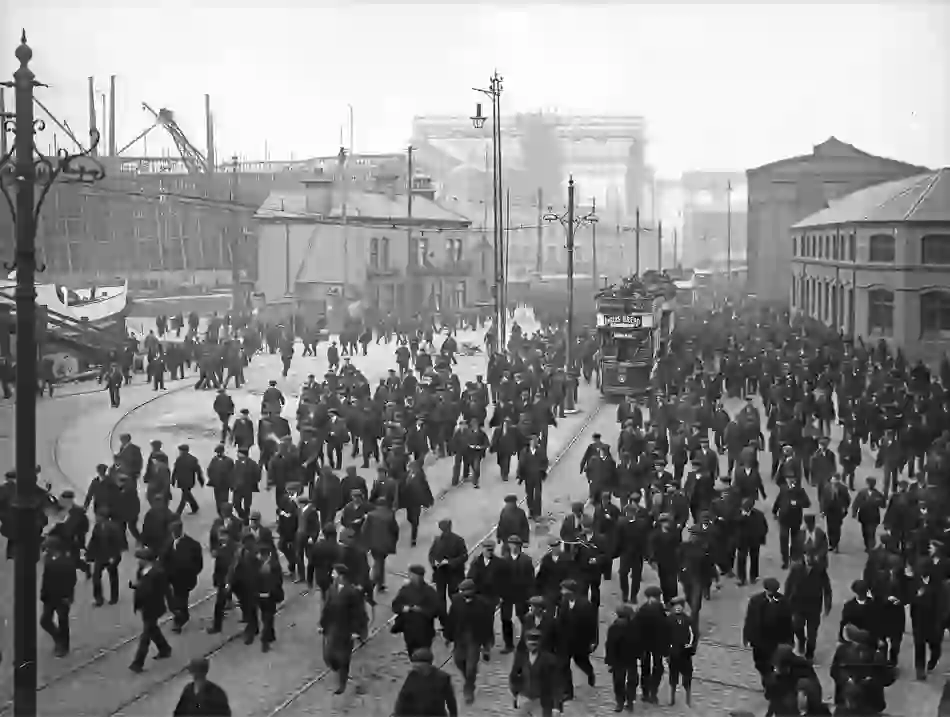

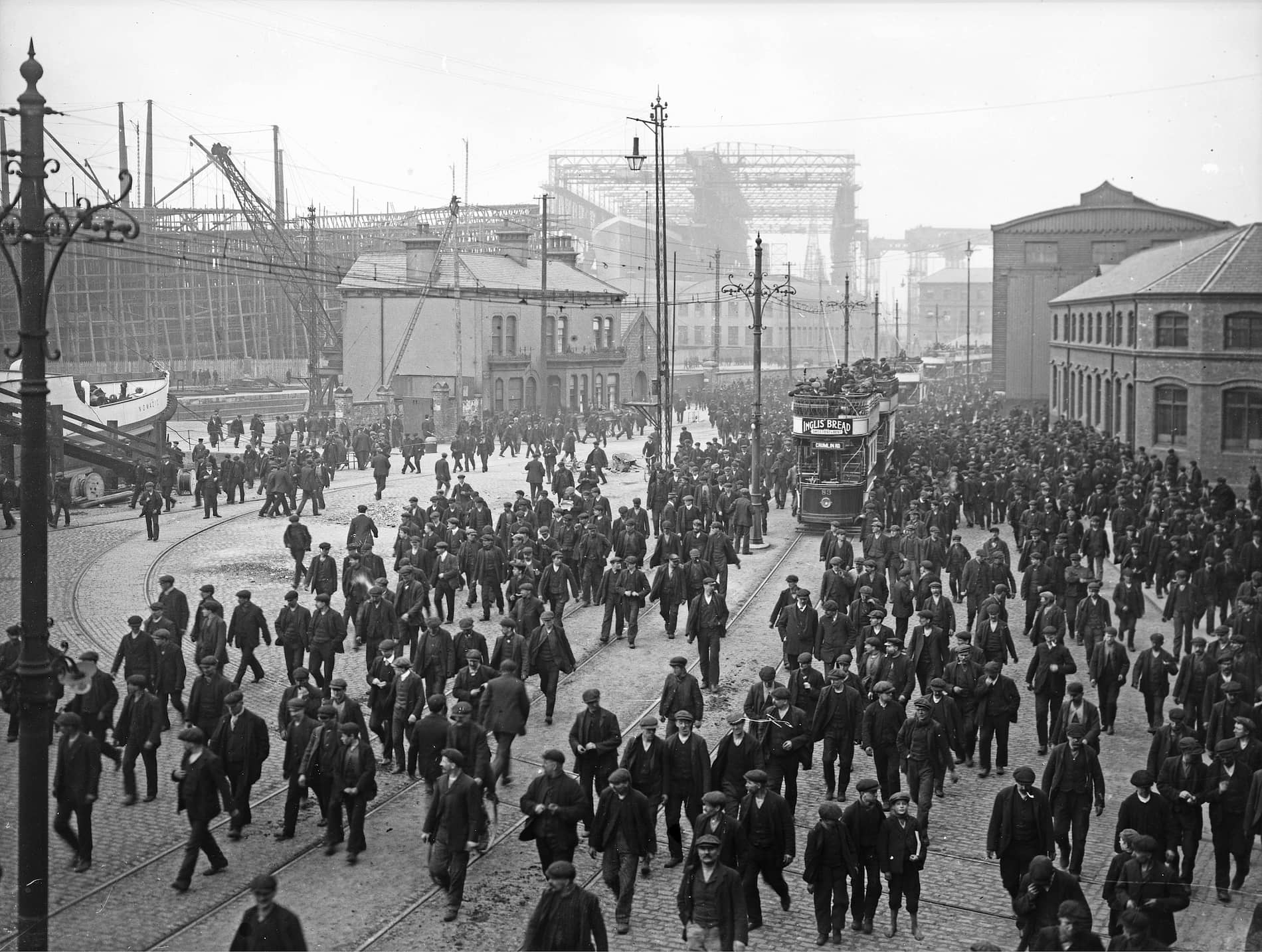

One shows a bustling Queen’s Road in 1911, with that distinctive hull taking shape under a giant gantry. Another is of the same area in the 1970s, featuring jagged mountains of scrap.

Donal Kelly, Belfast Mic Tours outside Titanic Belfast

“This is what I remember driving down Queen’s Quay back then,” Donal tells me. “There was essentially no tourism. You would have been a pretty brave backpacker.”

The different photos of the same sites are fascinating. When Titanic was built, Belfast was an industrial hub for the British Empire. In the 1970s and 80s, it was in heartbreaking decline.

Today, it is a tourist destination with mouth-watering restaurants, trailblazing street art, great shopping and museums. How did this slow-motion rollercoaster ride happen? How has the perception of Titanic changed in Belfast, and what do people here feel is her legacy in the city today, 110 years since this luxury ocean liner sailed away on the River Lagan?

Titanic in Belfast

L-R: Susie Millar, Titanic Tours Belfast; SS Nomadic, tender to RMS Titanic; Titanic Belfast; Titanic Pumphouse

A great story to tell

“In 1985, when [the wreck] was discovered, we wouldn’t have been able to sustain a tourism industry,” says Susie Millar, owner of Titanic Tours Belfast and President of the Belfast Titanic Society.

After 30 years of conflict, however, the Belfast Agreement of 1998 sealed a new era of peace. Coincidentally, a year earlier, a blockbuster movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet had catapulted Titanic into the popular imagination. A realisation was dawning: “We’ve got a great story to tell.”

Susie also has a personal connection to the ship. “My great-grandfather was the assistant engineer. His name was Tommy Millar. He had lost his wife early in 1912, so his reason for hopping aboard Titanic was that he was going to relocate over to New York city...

“He had two young children and he left them with relatives while he went off on this adventure. But of course, it didn’t turn out so well for him. The kids were left orphaned as a result.”

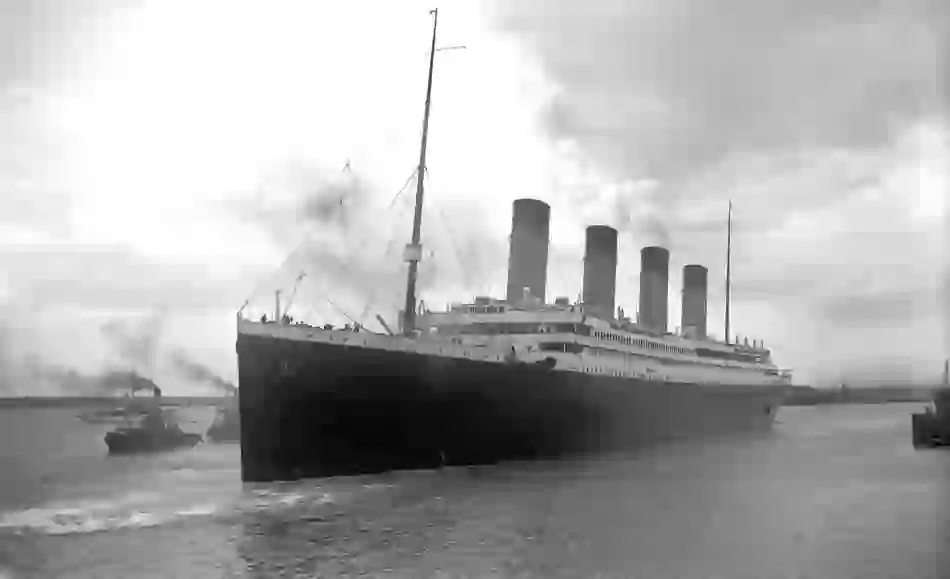

Titanic Leaving Southampton © National Museums NI, Ulster Transport Museum Collection

The biggest ship in the world

Titanic was built at Harland and Wolff as the second of three Olympic Class ships for the White Star Line. Back then, the Belfast shipyard was one of the biggest on the planet, spanning 80 acres on Queen’s Island and employing up to 10,000 people.

Harland and Wolff had built hundreds of ships, but Olympic, Titanic and Britannic were something else – engineering, technological and luxury marvels that stretched notions of what passenger liners could be.

“Tommy used to come home and tell his sons that he was working on the biggest ship in the world, and that they should be rightly proud of what Belfast was doing,” Susie says.

His youngest son, Ruddick, who was just five years old when Tommy sailed away, later wrote a book based on his story. “He just couldn’t understand how it was going to stay up in the water,” she says.

Queen's Road with shipyard men leaving work, Titanic in background, Robert John Welch (1859-1936) Harland and Wolff © National Museums NI

The 100,000 or so people who came to watch Titanic roll out of the Arrol Gantry into the River Lagan may have felt the same thing. The 269-metre, nine-deck liner would be dwarfed by the cruise ships of today, but she was a wonder of her times. (“The boat is unsinkable,” as Phillip Franklin of the White Star Line famously declared.)

Three million rivets had been mostly hand-hammered into place. In Titanic Belfast, the award-winning interactive museum, an immersive shipyard ride recreates the sights and sounds of the day. “Every ship cost a life, and there are lots of injuries besides,” a voice says. “The constant hammering, you could hear it all over Belfast.”

Nine months were spent fitting Titanic out in a dry dock, with joiners like Donal Kelly’s great-grandfather, engineers like Tommy Millar and hundreds of other craftsmen and workers finessing the ship. “The best room I’ve ever had on a ship,” one first-class passenger said of their stateroom.

Titanic had several styles and standards of stays, but the top end turns heads to this day – with four-poster beds, hot running water, marble sinks, electric heaters and five-star service just some of the frills. Among the provisions onboard were 8,000 cigars.

TITANICa exhibition at the Ulster Transport Museum, Belfast

TITANICa: a Titanic exhibition

Browsing through another exhibition, TITANICa at the Ulster Transport Museum just outside Belfast city, I see White Star Line plates and silverware in display cases. I also get a sense of why this ship, and this journey, continue to enthral.

The engineering marvel. The mysteries. The what-might-have-beens. Setting sail on her maiden voyage, Titanic was a floating snapshot of the Edwardian class system.

Some passengers, like John Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim (who were lost) and “the unsinkable Molly Brown” (who was not), were fabulously wealthy. Others had saved up to travel in the lower decks to new lives. And everyone had a story.

At TITANICa, I see a hot water bottle and nightshirt recovered from the seabed, along with a couple of perfume vials carried by Adolphe Saafeld, a German chemist who was bringing samples to drum up new business in America.

Stern view of completed ship in Belfast Lough with tugs, Robert John Welch (1859-1936) Harland and Wolff © National Museums NI, Ulster Transport Museum Collection

The “unsinkable” sinks

And of course, there is the Titanic disaster. Before the ill-fated ocean liner left Belfast, on March 31, 1912, Tommy Millar gave his son two pennies, with the instruction not to spend them until the family was back together again.

“But of course they never were,” Susie Millar says. Ruddick “stood on the shores of Belfast Lough and watched as Titanic sailed out past Carrick and Larne and turned the corner.” Her family still has those pennies today: “They were never spent”.

Titanic sank in the early hours of April 15, 2012. Ploughing ahead in an effort to reach New York ahead of schedule, she failed to avoid an iceberg in time. Marconi operators desperately tapped out old CQD and newer SOS signals, but it took less than three hours for the liner to snap in two and begin drifting 3.7km to the north Atlantic floor.

“Everyone around me just said, she’s gone,” one survivor said. The unsinkable had sunk, taking over 1500 people with her.

The tragedy soon hit front-pages. At Harland and Wolff, which had spent three years building Titanic, “there are stories of men weeping into pints after the news,” says Donal Kelly. There was outrage, inquiries, changes to safety practices at sea.

Titanic scenes from Belfast

L-R: Titanic mural; Titanic Memorial at Belfast City Hall; photograph of Titanic Drawing Offices in Titanic Hotel; hot water bottle recovered from seabed after Titanic sank

A taboo subject

Today, it feels like everybody knows the story. My kids have drawn pictures of Titanic in school. But that wasn’t always the case.

Two years after she sank, World War I broke out. Britannic ended up as a hospital ship. The story would slip from conversation – not least in Northern Ireland.

“Titanic was a taboo subject”, Donal Kelly says. “As a teenager growing up in Belfast, this was never talked about outside of our house,” Susie Millar adds. “We had built this fantastic ship and it had lasted 13 days and then was at the bottom of the ocean.

“There was a sense of embarrassment about it… did we do something wrong? Was it our fault? Was it our pride that was being punished?

“All those sort of emotions were floating around. And when I was growing up, there were a lot of other things going on in Belfast… never mind a sunken ship.”

Viewing footage of Titanic's final resting place at Titanic Belfast © Tourism Ireland

The wreck of the Titanic was discovered in 1985, when oceanographer Robert Ballard followed a debris field to find a ghostly prow that looked like it was ploughing through the seafloor (“It was as if the Titanic was still trying to get to New York City”, he said). But Northern Ireland’s Troubles ensured any talk of celebrating Belfast’s role in the story, or even talking about tourism, was a pipedream.

The last ship launched from the Queen’s Yard in 1968. The slipways were filled as a car park; the economy was in decline.

Even in the 1990s, when I first began visiting the city, friends that lived there told me to avoid eye contact. Shops closed at lunchtime on Saturdays. I wasn’t writing travel stories about it.

Belfast City Hall seen from the Observatory at the Grand Central Hotel

Changing times

But things changed. In 1997, James Cameron’s Titanic film came out, a bona fide event movie that everyone went to see. A year later, the Belfast Agreement was signed, sealing a peace process that had once felt unimaginable. Belfast didn’t blossom overnight. But suddenly, it felt like blossoming was possible.

“Belfast 2.0” was a story headline I loved writing in the 2000s. Change was complex, and clunky, of course – it always is. But instead of talking about conflict, I could write about food and shopping.

Visitors could take Black Taxi tours of its political murals. Lady Gaga and Adele jetted in for the MTV Europe Music Awards.

New builds such as the Victoria Square shopping centre and The Odyssey (now the SSE Arena) sprung up alongside developments like the Metropolitan Arts Centre (MAC) and five-star Merchant Hotel. Heck, the city even got an ice hockey team. And then, 100 years after Titanic launched, came the game-changer.

Titanic Belfast

Titanic Belfast: a hero attraction

“Titanic Belfast has been the catalyst for the tourism industry in Northern Ireland in the past 10 years,” says Eimear Kearney, its head of marketing, whom I meet after touring the galleries. Previously, people “had been embarrassed and a wee bit ashamed to talk about Titanic because it was seen locally as a failure”, Eimear says.

But today, this visitor attraction also shines a spotlight on the people who built the ship and the times in which they built it. “It was a turning point for the city. We needed to start talking about ourselves in a more positive light,” she says.

Built as a public/private partnership, and owned by Maritime Belfast Trust, a charity responsible for preserving and promoting the city’s maritime heritage, Titanic Belfast reminds me of the Guggenheim Bilbao – both in its shimmering skin (at over 38 metres, its aluminium-clad “hulls” are the same height as Titanic’s) and as a catalyst for tourism development.

Cobh in County Cork, Cherbourg and Southampton all have strong connections with the ship, but Titanic Belfast has made Belfast the global hub of Titanic tourism.

Titanic Belfast

L-R: inside Titanic Belfast; Titanic Belfast at night; interactive video display at Titanic Belfast; artefacts from Titanic's history

The Titanic Belfast experience

On my visit to Titanic Belfast, I take the shipyard ride, see replica cabins, learn about life in Belfast in 1912, watch wreck site footage from Ballard’s subs, step aboard the actual SS Nomadic, – a tender that ferried passengers from Cherbourg, which you can visit separately – and read quotes from famous visitors.

“Belfast is a different city,” reads one from former US President Barack Obama. “Once-abandoned factories are rebuilt. Former industrial sites are reborn. Visitors come from all over… So to paraphrase Seamus Heaney, it is the manifestation of sheer, bloody genius. This island is now chic.”

There’s no doubting this building’s galvanising effect as a hero attraction that has brought in 6.5 million visitors from over 145 countries in its first decade. “The big silver magnet,” as Donal Kelly calls it.

Lagan Bridge, Belfast

The Maritime Mile

“The 100th anniversary [in 2012] was always the key date,” Susie Millar says. “We had to have something as a product that would attract a worldwide audience, and that was achieved.

“But it’s not all about that building. It’s about what’s been done with the waterfront, what they now call the Maritime Mile. It’s become a destination that you can spend three or four days in.”

That’s the truth. Where once, Titanic talk was taboo, today the story of this ship and the city that built it have been embraced, helping to create a rising tide for tourism.

There have been festivals, Michelin stars and reboots of the Cathedral Quarter and east Belfast’s CS Lewis Square. I can get great coffee, take a food, drink or music tour (Did you know Led Zeppelin first played Stairway to Heaven live at Ulster Hall?), visit an urban Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking area) in west Belfast, or drink a cocktail made with local Shortcross or Jawbox craft gin in Ireland’s highest bar, at the Grand Central Hotel.

Belfast city

L-R: Commerical Court; the Muddler's Club; Ox Restaurant; Conor McClelland, Rayanne House

A Titanic menu

“After 30 years of hell, I think it was just the right time,” says chef Conor McClelland, who runs luxury guesthouse Rayanne House with his wife Bernie in Holywood, just outside Belfast city. “I think it all just sort of fell in. The more tourists, the more restaurants that were needed… it was a combination of everything.”

Rayanne is a Victorian house overlooking Belfast Lough, and Conor has been cooking up his Titanic Menu, a feast for “Titanoraks”, as he calls them, since 2010. “It’s a replica of the very last dinner that was served to first-class passengers,” he explains – a nine-course extravaganza with dishes ranging from a cream of barley soup finished with Bushmills whiskey and cream to poached salmon with Mousseline sauce and pan-seared filet mignon topped with foie gras and truffle.

Titanic Last Meal, Rayanne House, Belfast

The menu was meticulously recreated from surviving recipes and menus, and is served in a period room bedecked with replica china, pink roses and white daisies. “It’s surprising how a menu that’s over 100 years old still works today,” he says of the French-influenced fare. “It was a fabulous menu… very decadent”.

A growing confidence and quality in Irish food also means Conor can source most of his ingredients from the island, and I’m intrigued to learn that Bernie’s family, who had been involved in the fruit business in the early 1900s, actually supplied fruit to the Titanic. “You’re also looking out on Belfast Lough, so you can literally imagine the Titanic sailing up and down for trials,” Conor says.

Titanic Hotel, once the Headquarters and Drawing Offices of Harland and Wolff

Titanic Hotel

My bed for the night joins more dots. The Titanic Hotel incorporates the old Harland and Wolff drawing rooms and original features like the directors’ offices, iron staircase and a chief draughtsman’s booth in the Wolff Grill.

As I tuck into a halibut dish with curry and lobster hollandaise inside, I read a panel about the booth, colloquially known as “the bollocking box” because anyone summoned there usually got an earful.

The hotel walls are decorated with White Star Line posters and monochrome photos of the ship, and original clerks’ desks have been turned into display cases showing period instruments and documents. “It’s a little bit of a museum itself,” the receptionist quips.

The famous booth in the Titanic Hotel, Belfast

“The great success story here is the hotel,” says Colin Cobb of Titanic Belfast Tours, another guide I meet. He proclaims it “tastefully restored”. Colin’s been doing tours for years, and gives me a realistic, honest assessment of how far he feels Belfast has come, and how far it has to go.

We follow the Maritime Mile out along the river, past Titanic Belfast, art installations, rusty chunks of the last remains of the original Arrol Gantry and spaces awaiting future development. Our last stop is the original Pump House, part of which will host a new whiskey distillery, and the dry dock where the ship was fitted out. It’s an eerie footprint. “The last place Titanic ever rested on dry ground,” Colin muses.

Titanic Belfast and the old Harland and Wolff Headquarters and Drawing Offices – now the Titanic Hotel

Titanic’s legacy

It’s amazing how many people and places this tragic ship has touched. Back at the end of the slipway plaza, I watch a little moorhen plop into the water where Titanic would have done over a century ago. It's a place Susie Millar still comes on the anniversaries to reflect, and the spot Donal Kelly ends our tour, after that little game of pitch and toss.

Over a century since their great-grandfathers worked on the ship, it feels like Titanic’s legacy is as much one of industrial prowess as it is of storytelling and the rise of a 21st century city.

“20, 30 years ago it was a very hard sell trying to get people to come here,” Donal muses.

It’s a different story today.

Pól Ó Conghaile is Travel Editor with The Irish Independent.

Thérèse Aherne is a photographer based in Dublin.